The Unsung Hero of the Katana: Understanding the Tsuba Handguard

When most people picture a samurai sword, they think of the sweeping curve of the blade and the razor edge catching the light. But ask any serious sword enthusiast or collector and you’ll often hear something surprising: the “personality” of a sword is frequently revealed by its handguard – the tsuba.

You can think of the tsuba as the katana’s business card and safety helmet combined. It protects your hand, helps balance the weapon, and quietly showcases the taste of the owner and the skill of the metalworker. On many antique swords, the blade stays hidden in the scabbard, but the tsuba is always visible – a small circle of metal that tells a much bigger story.

Much like a surfboard fin, a guitar pickup, or a custom wheel on a car, the tsuba is a small component with a huge impact.

In this article, we’ll break the tsuba down into four clear sections:

-

Functional overview

-

Component breakdown

-

Styles & schools

-

Appreciation & collecting tips

We’ll stay focused on craftsmanship, materials and design – no cultural or political commentary, just metal, structure and art.

Functional Overview: What the Tsuba Really Does

At first glance, the tsuba looks like a decorative disk. In reality, it’s a carefully engineered part of the sword. A well-made tsuba quietly performs four core functions every time the sword is used.

1. Hand Protection

The most obvious job: keep your hand away from the edge.

-

During cuts or blocks, the tsuba acts as a physical barrier between your fingers and an opponent’s weapon.

-

If your grip shifts forward under impact, the tsuba stops your hand from sliding onto the sharp blade.

It’s not a full shield, but it can easily be the difference between a controlled strike and a self-inflicted injury.

2. Balancing the Blade

The tsuba is part of the sword’s weight distribution system, not just a flat plate stuck in the middle.

-

A slightly heavier tsuba pulls the point of balance closer to your hand, making the sword feel quicker and easier to control.

-

A lighter tsuba allows for a more blade-heavy feel, which can hit harder but takes more effort to recover.

It’s similar to tweaking the balance of a cricket bat, golf club, or fishing rod: small changes in weight placement can dramatically change how it behaves in your hands. Good makers select or design a tsuba to match the blade’s geometry and intended use, not just for looks.

3. Sweat Barrier & Grip Protection

Training, test cutting and demonstrations all have one thing in common: sweaty hands.

-

The tsuba sits between your palm and the tang (the part of the blade hidden inside the handle).

-

It helps slow down how much sweat reaches the tang and the core of the handle, where moisture can encourage corrosion over time.

It’s not a watertight seal, but it’s a useful buffer. Over years of regular use, that extra layer between your hand and the tang can make a noticeable difference to longevity.

4. Sheathing Control – The “Stop” for the Blade

When you slide a katana back into its scabbard (saya), the first thing that meets the mouth of the scabbard is the tsuba.

-

It acts as a firm stop, preventing you from ramming the blade too far in and damaging the tip or the inside of the scabbard.

-

When drawing, many practitioners “thumb the tsuba” – using the thumb to nudge the guard and break the seal before the full draw.

So the tsuba is quietly involved in smooth, safe sheathing and drawing, not just combat moments.

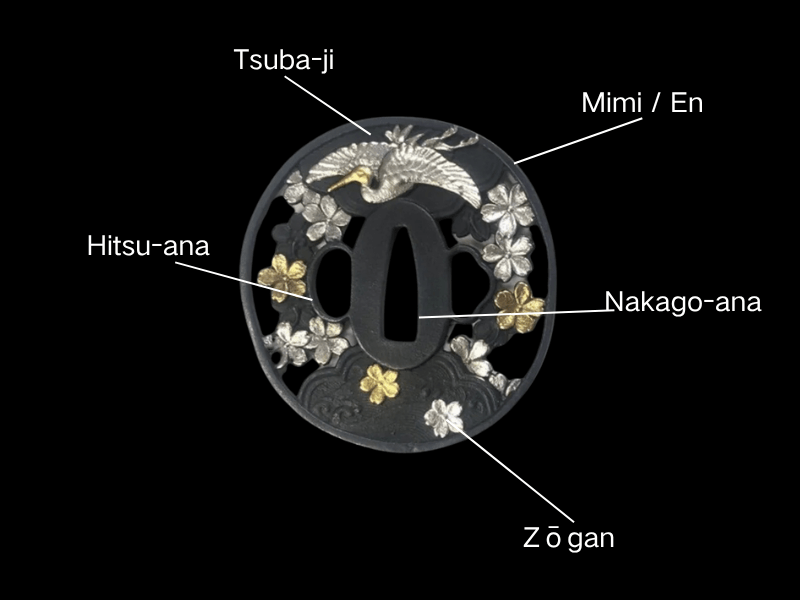

Anatomy of a Tsuba: A Metal Map in Miniature

Pick up a tsuba and turn it over in your hand and you’ll quickly see it’s not just “a round piece of metal”. It’s a small, sculpted landscape with clearly defined regions, each with its own name and function. Here are the main elements you’ll see mentioned in descriptions and listings.

Tsuba-ji (鍔地) – The Base Plate

The tsuba-ji is the main body of the tsuba – the plate itself.

-

Typically made from iron, mild steel, or copper-based alloys (such as brass or darker copper mixes).

-

Thickness varies from thin and refined to thick and robust.

-

The surface may be smooth, hammer-textured, forged, or deliberately patinated.

If the tsuba were a painting, the tsuba-ji would be both the canvas and the background colour.

Mimi / En (耳・縁) – The Rim

The outer edge of the tsuba, known as the mimi or en, frames the whole piece.

-

A thick, rounded rim feels solid and durable, and helps absorb knocks and bumps.

-

A thin or beveled rim looks lighter and more elegant, but sacrifices some impact resistance.

-

Rims are often decorated with file marks, rope-like patterns or subtle chiselling.

Collectors often comment that a piece has a “good rim” when the edge is even, confident and comfortable in the hand.

Hitsu-ana (櫃孔) – Openings for Utility Tools

Many tsuba include one or two smaller side openings called hitsu-ana.

-

Traditionally, these allowed small tools like a kozuka (small knife) or kogai (hair/armour pick) to share the scabbard with the main blade.

-

On modern swords, the tools are often omitted, but the hitsu-ana remain as part of the classic layout.

Design-wise, these openings act as negative-space accents, breaking up the plate and adding rhythm to the composition.

Nakago-ana (茎穴) – Central Tang Slot

At the centre is the nakago-ana, the slot where the tang of the blade passes through the tsuba.

-

The fit must be secure: if it’s too loose, the tsuba can rattle; too tight and mounting becomes a problem.

-

Soft metal inserts called sekigane may be added to fine-tune the fit.

On quality pieces, the nakago-ana is cleanly cut and neatly finished, showing that function and fit were taken seriously.

Sukashi (透かし) – Openwork

Sukashi refers to openwork, where sections of the plate are cut out to create a design.

-

Patterns range from simple geometric shapes to complex vines, waves, animals or abstract forms.

-

At its best, sukashi can look like metal lace – visually light, structurally sound.

-

Removing material also reduces weight, which directly affects how the sword balances.

Sukashi is a test of planning and restraint: cut away too little and the design looks clumsy; too much and the guard becomes weak.

Zōgan (象嵌) – Metal Inlay

Zōgan is the technique of inlaying contrasting metals into the surface of the tsuba.

-

Common inlay metals include gold, silver, copper, brass and their alloys.

-

The maker chisels shallow recesses into the base plate, hammers in the softer metal, then refines the details.

-

Inlay can be subtle – a few tiny highlights – or bold, with large, bright areas of metal.

When a tsuba flashes with different colours under the light, that’s often zōgan at work – the metalworker’s version of adding highlights with a fine brush.

Styles & Schools: Different Looks for Different Tastes

Even if you ignore symbolic meanings, tsuba come in a huge variety of visual styles. Understanding the basic shapes and a few broad stylistic families makes it much easier to choose a guard that suits both your sword and your eye.

Common Outline Shapes

Most tsuba fall into a handful of classic outlines. The Japanese names sound exotic, but the shapes themselves are straightforward.

Maru-gata – Round

-

The standard round tsuba.

-

Visually neutral and balanced; works well with almost any blade.

-

An ideal starting point for beginners because it’s so common and versatile.

Mokkō-gata – Four-Lobed / “Melon” Shape

-

Looks like a four-petal flower or a slightly pinched four-leaf clover.

-

The flowing inward curves give it a sense of movement and softness.

-

Pairs nicely with organic themes like waves, leaves and vines.

Kaku-gata – Square / Angular

-

Built from straight edges and corners.

-

Feels bold and architectural – more industrial in character than a simple circle.

-

Corners are usually softened so they don’t catch on clothing or the scabbard.

There are many other outline types, from ovals to gourd shapes, but these three cover the majority of guards you’ll encounter in mainstream markets and collections.

Stylistic Families and Regional Traditions

Instead of diving deep into historical backgrounds, it’s more practical here to talk about stylistic families – broad approaches to design and metalwork that you’ll see repeated.

1. Refined Figurative Work – “Nara-style”

Some schools and workshops became famous for detailed figurative scenes: people, animals, landscapes.

-

Expect fine carving, layered relief, and generous use of inlay.

-

Surfaces are busy but, at their best, still read clearly from arm’s length.

If you like the idea of a tsuba functioning as a tiny metal “story panel”, this style will resonate with you.

2. Rustic Iron Elegance – “Higo-style”

Other makers emphasise plain iron and clean design.

-

Dark, matte surfaces with subtle texture, minimal decoration, and strong silhouettes.

-

Motifs are understated – a few leaves, a simple crest, a sparse pattern.

-

The appeal is similar to a well-used cast-iron pan or a favourite leather belt: practical beauty with personality.

For practitioners who want a tsuba that looks serious and functional on a training sword, Higo-style pieces (or modern interpretations) are often an excellent match.

3. Urban Workshop Refinement – Decorative Edo Styles

As swords became formal dress items rather than battlefield tools, many city-based workshops focused on highly decorative guards.

-

Often built on soft-metal bases with rich artificial patinas.

-

Heavy use of carving and zōgan, with extremely fine, jewellery-like detail.

-

Ideal for display swords or high-impact showpieces.

If you want a sword that doubles as décor – something that looks at home in a living room, office or showroom – this polished, decorative style works very well.

Appreciation & Collecting: A Practical Guide for Beginners

Whether your sword interest sits alongside other hobbies or is your primary passion, the basics of tsuba appreciation are easy to learn. You don’t need specialist training – just time, comparison and curiosity.

1. Check the Fundamentals Before the Fancy Stuff

Before you get drawn into gold highlights and complex carvings, look at the basics:

-

Is the plate structurally sound – no cracks, deep chips or major distortions?

-

Does the rim feel even and deliberate all the way around?

-

Is the nakago-ana neatly shaped, with no ragged, rushed filing marks?

A heavily decorated guard with weak fundamentals is like a car with an expensive paint job but no chassis – not what you want on a working sword.

2. Judge It at a Distance and Up Close

Use a simple two-step test:

-

Hold the tsuba at arm’s length. Does the design read clearly, or does it collapse into visual clutter?

-

Bring it closer and look at the edges, lines and transitions. Are they crisp and confident, or soft and muddy?

High-quality, hand-worked tsuba usually show decisive tool marks and clean edges, rather than the slightly melted look of cheap cast reproductions.

Online buying tip:

When viewing photos, always zoom in on the rim, the edges of any sukashi, and the boundaries of inlay. These areas often reveal the true level of workmanship.

3. Learn to Recognise Patina vs Rust

Time leaves a mark on iron, but not all colour changes are desirable.

-

Patina is a stable, even surface tone – anything from deep brown to blue-black – that enhances depth and character.

-

Active rust is flaky, powdery or bright orange-red and tends to eat into details rather than sit on the surface.

If you live in a humid or coastal environment, store tsuba in a dry, stable place. A very light oil on iron pieces can help maintain patina and keep active rust at bay.

4. Be Clear About Your Goal and Budget

Ask yourself honestly:

-

Is this tsuba destined for a regular training sword?

-

Is it mainly a display piece on a stand or mounted sword?

-

Are you slowly building up a serious collection of antiques?

For training, prioritise strength, fit and safe edges over signatures and rare names.

For display, you can lean more heavily into striking visuals.

For collecting, the best investment is often education first, purchases second – study, compare, ask questions, and you’ll make better decisions long term.

5. Common Pitfalls to Avoid

A few practical warnings for newcomers:

-

Cheap cast reproductions – often with repeated designs, fuzzy details and flat-looking surfaces. Fine for budget blades, but don’t mistake them for hand-crafted work.

-

Over-cleaned guards – if an old iron tsuba shines like new cookware, its original patina may have been stripped off, which usually hurts both character and value.

-

Heavily altered pieces – watch for badly hacked tang slots, obvious welds or aggressively reshaped rims; these can indicate forced fitting or repair work that compromises strength.

When you’re unsure, lean on reputable dealers, experienced collectors, or local sword/martial arts communities. A second opinion can save you a lot of money and regret.

Conclusion: A Universe of Craft in a Small Circle of Steel

Next time you see a katana – in a dojo, in a collection, or on your own sword rack – try this:

before you admire the curve of the blade, let your eyes rest on the tsuba.

Inside that small circle you’ll find:

-

Function – guarding your hand, tuning the balance, buffering sweat, guiding the blade into and out of the scabbard.

-

Engineering – thoughtful choices about thickness, cut-outs and weight distribution.

-

Artistry – textures, lines, openwork and inlay turning metal into sculpture.

For sword enthusiasts, fans of Japanese blades, and beginner collectors alike, learning to “read” a tsuba is like learning to taste coffee properly: once you understand what you’re looking at, you can never go back to seeing it as “just a ring of metal”.

So the next time you appreciate a samurai sword, don’t skim past the guard. Pause, turn it gently in the light, and give this small component the attention it deserves – because in that modest circle of steel lives a self-contained universe of craftsmanship, measured not in metres, but in millimetres.