Why Can a Katana Break?

A Comprehensive Look from Metallurgy to Combat Mechanics

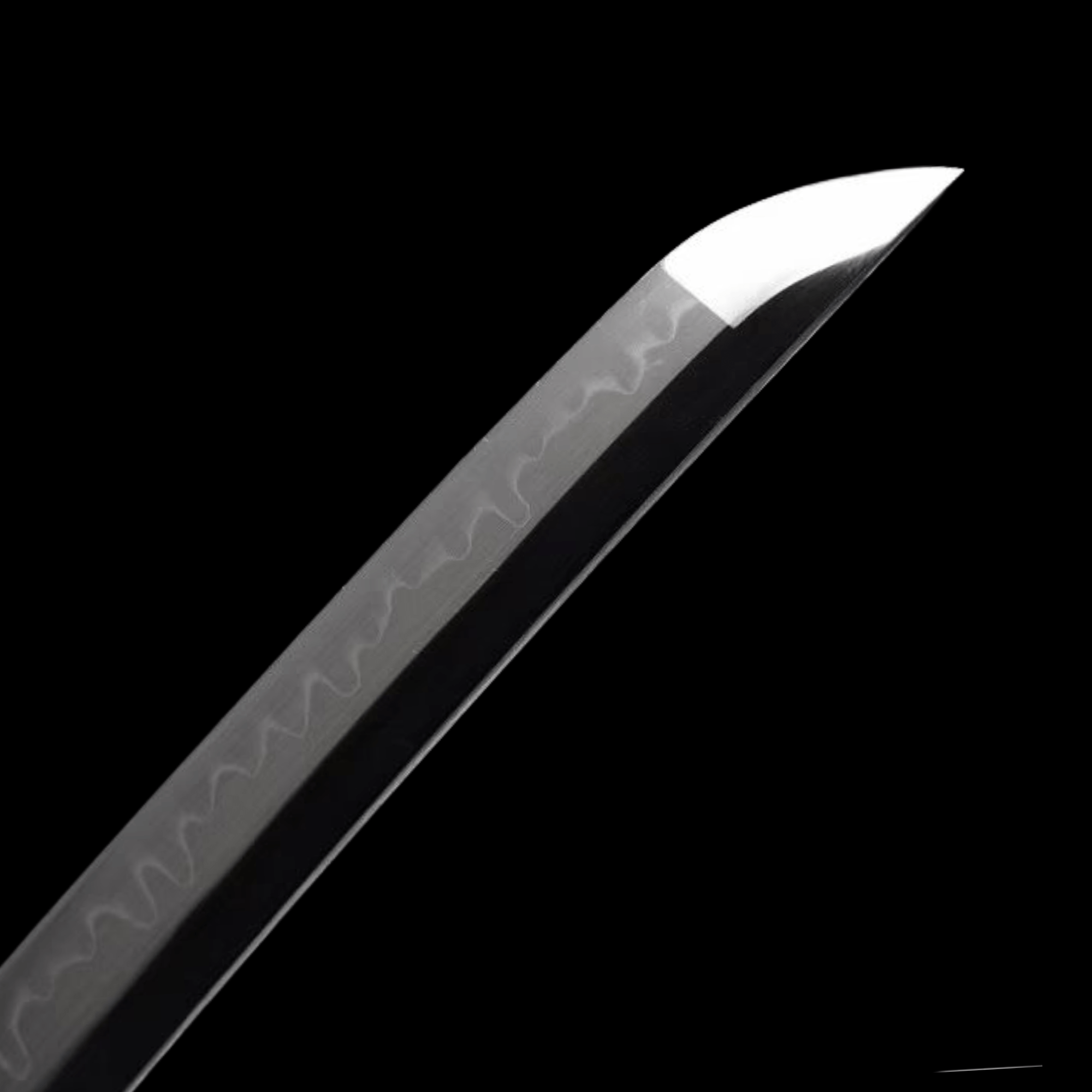

The Japanese katana is often regarded as a perfect blend of sharpness, elegance, and spiritual craftsmanship. Its graceful curve, distinct hamon (temper line), and refined forging techniques make it one of the most iconic swords in the world.

However, even the finest katana is not unbreakable.

Under improper use, extreme conditions, or hidden structural flaws, a katana can crack or break. Understanding why this happens requires looking closely at its metallurgical structure, mechanical stress, usage methods, and maintenance practices.

1. Metallurgical Structure: The Balance Between Sharpness and Toughness

At the heart of the katana lies the principle of differential hardening (Yaki-ire).

-

The edge is rapidly quenched to form martensite, an extremely hard but brittle structure.

-

The spine cools more slowly, retaining pearlite and ferrite, which remain softer and more flexible.

This combination gives the katana its legendary balance of strength and resilience — able to slice cleanly through targets without deforming.

But if the tempering is imbalanced — for example, if the edge becomes too hard or the blade insufficiently tempered — the result can be brittleness and fracture.

In essence, a katana’s power comes from the delicate harmony between a hard cutting edge and a resilient spine.

Too much hardness without proper tempering leads to cracks and breaks.

2. Mechanical Stress and Directional Weakness

The katana is designed primarily for cutting (slashing), not for chopping or striking.

When subjected to lateral or twisting stress, the blade is highly vulnerable to breakage.

Common stress concentration points include:

-

Machi area – the transition between blade and tang (nakago).

-

Hamon region – where hard and soft steel meet, creating potential microcracks.

-

Mekugi-ana – the peg hole on the tang that reduces cross-sectional strength.

A katana is strong along its cutting line, but fragile across it.

Lateral stress is its greatest enemy.

3. Usage Scenarios: Misuse Leads to Breakage

1. Side Impact

Striking hard objects such as metal, stone, or dense wood introduces immense side stress, which can cause the blade to snap instantly.

2. Incorrect Cutting Angle

A deviation of even 10° from the proper cutting line during tameshigiri (test cutting) can create uneven stress distribution, resulting in chipping or breakage.

3. Improper Target Material

Katanas are intended for soft targets such as tatami mats or bamboo poles.

Using them to cut steel, concrete, or bone is a common cause of destruction.

Remember: a katana is not an axe — it was never designed to smash.

4. Manufacturing and Maintenance Issues

1. Structural Flaws

Poor lamination or internal impurities can create hidden weak points.

Incomplete forge welding or trapped air bubbles may cause cracks to form under stress.

2. Heat-Treatment Errors

Over-quenching makes the blade extremely hard but brittle.

If not properly tempered, residual stress can accumulate and eventually cause the blade to fracture on its own.

3. Corrosion and Fatigue

Rust weakens the steel’s microstructure, especially around the tang or machi area.

Repeated cutting over time can also create microscopic fatigue cracks that suddenly propagate into a break.

Even a tiny flaw, under repeated stress, can become a catastrophic fracture.

5. Environmental Factors

-

Low temperatures reduce the toughness of steel, making it more prone to breaking.

-

Moisture and humidity lead to corrosion, especially when the blade is stored in the scabbard for long periods.

Proper storage and maintenance are essential to preserve the integrity of a katana.

6. Historical and Practical Insights

In Japan’s Sengoku (Warring States) period, there was a saying:

“Hitotsu tatakai, hitotsu ore” — One battle, one broken sword.

This reflected the harsh reality of warfare, where even master-forged swords could break after striking armor or another blade.

During the Edo period, swordsmiths shifted focus toward creating blades for decisive, single cuts, prioritizing sharpness over indestructibility.

Even in modern tameshigiri, expert practitioners sometimes break blades due to poor angle control or inappropriate targets.

7. Modern Improvements

Contemporary craftsmanship has greatly increased a katana’s durability through modern metallurgy:

-

Use of spring steel, T10 high-carbon steel, and L6 bainite steel for superior resilience.

-

Vacuum heat treatment and isothermal tempering to reduce internal stress.

-

Iaito practice swords made from aluminum-zinc alloys or unquenched steel for safety and flexibility.

Today’s well-forged katana combines the soul of tradition with the strength of modern technology.

8. Conclusion

| Category | Common Cause | Typical Result |

|---|---|---|

| Metallurgical | Uneven hardening, excessive hardness | Brittle fracture |

| Mechanical | Lateral stress, stress concentration | Structural break |

| Improper Use | Wrong angle, hard targets | Sudden snap |

| Manufacturing | Impurities, poor forge welds | Internal cracking |

| Environment | Rust, cold temperature | Fatigue or corrosion failure |

A truly fine katana is not defined by being unbreakable,

but by achieving the perfect balance of sharpness, resilience, and craftsmanship under proper use.

As an old Japanese saying goes:

“A sword reflects the heart of its wielder.”

The beauty and strength of the katana mirror the discipline and spirit of the one who wields it.